We need to fundamentally alter the course of our policies in Australia and New Zealand in order to fix the longstanding issue of housing affordability. COVID-19 has revealed issues that have always been there. Before the pandemic, our issues were cracks in the foundations of our house of cards. We noticed them, thought to ourselves, “We better do something about that before it gets worse”. Then 2020 came along.

The pandemic exposed problems within our society that were most likely glaringly obvious to those who operate within them. People suddenly realised that our teachers and nurses are fundamental to society; check-out operators, truck drivers, cleaners and hospitality staff. But one issue the pandemic truly exposed is the rising inequality within our societies. In its October 2020 issue of World Economic Outlook, the International Monetary Fund found that “The pandemic will reverse the progress made since the 1990s in reducing global poverty and will increase inequality.” Australia is no different.

Real-estate agents gloat and celebrate when a house sells $100,000, $200,000 over reserve; yet every bang of the gavel is another nail in the coffin that is our access to affordable housing.

According to the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC), ‘Poorer Australians four times more likely to die from a COVID-19 infection‘. Those from low-socioeconomic backgrounds were more likely to have jobs where they couldn’t work from home and often have less access to healthcare. Part-time and casual workers are still struggling with reduced hours and according to Anglicare Australia’s 2021 snapshot, almost 800,000 Australians lost their jobs entirely.

According to a joint “Australian COVID-19 policy responses A health equity report card” report by the Australian National University (ANU) Menzies Centre for Health Governance, “Health inequities are produced (and prevented) by policies and actions primarily outside the health sector: employment, income support and housing are three of the most important determinants of health inequities.”

“Precarious employment, inadequate income support and housing stress is detrimental for physical and mental health, and the likelihood of experiencing these health impacts is greater for those lower down the social hierarchy.”

Housing affordability

Thankfully for us, the pandemic exposed the capability of our national governments’ ability to plan, listen to experts, to adapt and respond to issues quickly. Housing affordability and access to good, warm housing is an ongoing issue that has practically been ignored for decades. Real-estate agents gloat and celebrate when a house sells $100,000, $200,000 over reserve; yet every bang of the gavel is another nail in the coffin that is our access to affordable housing.

In essence, the pandemic is an opportunity to change our future. We shouldn’t just “snap back” to life before the pandemic because Australia and in effect, New Zealand, has an opportunity to reassess and move towards a roaring twenties period of economic growth and prosperity. However, its becoming increasingly likely that Australia will miss this opportunity when it comes to investing in our housing market to ensure Australians have access to affordable housing.

Housing in Australia and New Zealand – A snapshot

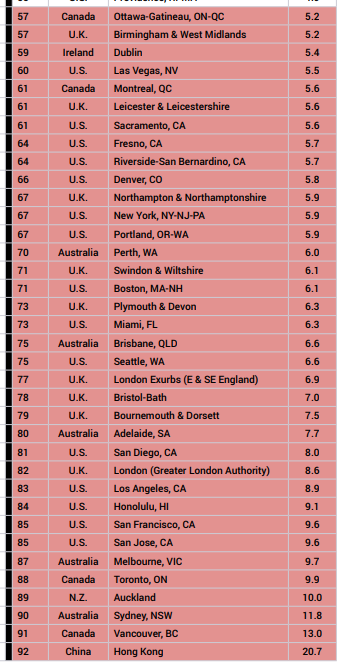

Low-income households in New Zealand are likely to be spending more than 50% of their disposable income on rent and more than 40% of their disposable income on a mortgage. In the Demographia International Housing Affordability 2021 Edition, both Australia and New Zealand’s housing market was rated as “severely unaffordable”. Perth, Brisbane, Adelaide, Melbourne, Auckland and Sydney all rank as “severely unaffordable”.

According to the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), in 2017–18, 11.5% of households spent 30% to 50% of gross income on housing costs with another 5.5% spending 50% or more (ABS 2019). Rental housing in Australia is insecure, with leases often being 6 to 12 months. In comparison, Denmark and the Netherlands “have indefinite and fixed-term leases where it is difficult to terminate the fixed-term lease without the tenant’s permission”.

Since the beginning of the pandemic in 2020:

- Just over 63% of renters experienced changes to their employment, including reduced hours and/or income, reduced income and temporary lay-off.

- Around one-third experienced worse living circumstances including difficulty paying rent and/or bills.

- About 25% of renters skipped meals to save money.

- Since the start of the pandemic, over 5% reported that they had received an eviction notice (Baker et al. 2020b).

- Around 17% reported that their rent became unaffordable (Baker et al. 2020a).

Source: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2021

Report card: ‘F’ to Australia’s Federal Government for housing policy

The New Zealand Government’s 2020 Housing Package aimed to address housing affordability through a range of tax measures, including the introduction of what is effectively a capital gains tax. The package raised the income and house price cap for its First Homebuyer’s Grant scheme and directed funds to their social housing agency Kāinga Ora to boost social housing acquisition. For Australia, the Federal Government has missed an opportunity to invest in social housing and develop policies to ensure Australians have access to affordable housing. The Federal Government did practically nothing except provide an opportunity for homeowners to renovate their homes who could already afford major renovations.

COVID-19 provided an opportunity to radically challenge our way of addressing policy problems due to the large-scale nature of the issue. It provided an opportunity for radical change and ‘thinking outside the box’ to solve complex problems like housing availability and affordability. Providing a targeted policy to those who can already afford renovations will be detrimental to the long-term outcome of Australia’s housing affordability.

What needs to be done?

Policies need to be enacted and directed by the Federal Government which systemically address housing issues. According to the Menzies Centre for Health Governance, Australia needs a National Health Equity Strategy and should introduce a Green Social Housing Economic Stimulus Package to build social housing units that adequately address accessibility, cultural adequacy, infrastructure and environmental sustainability.

Investing in good quality social housing and providing housing stock that is affordable is what Australia’s renters need. Housing is a human right, not an investment opportunity. Australian citizens should not be choosing whether to pay rent or put food on the table.

In an upcoming article, we will look to Vienna, Austria where social housing has become paramount in ensuring its citizens have access to good and affordable housing.